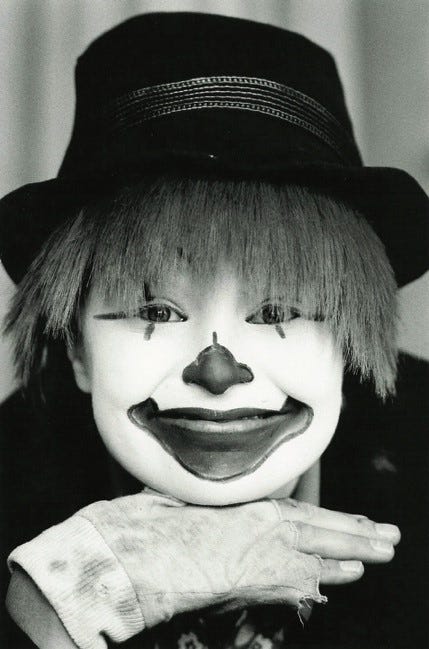

Pierrot, Play & Falsies

On when clowning, humour & play began taking over my life.

In this issue: I began to realize that mime and clowning were not just modes of performance but also tools for health and healing. Performing as a clown was shifting my approach to raising a family and teaching drama. When had I lost my sense of humour?

Pierrot at School

When I entered a gym in a rural elementary school as Pierrot the mime clown, I noticed a few older boys who did not look impressed by the clown. The younger children were laughing at the clown’s antics but the older boys were rolling their eyes and looking sideways at each other. I knew that my show could not work without the boys’ engagement. Pierrot went over to interact with the boys. She threw a boy one the end of a mime rope and challenged him to a rope pull. All eyes were on him. He slowly stood up and pretended to hold the end of the rope. Clown and boy engaged in a frantic tug of war and of course the boy won, much to the clown’s chagrin. Another boy took the rope. The clown lost again, but everyone was laughing. As I began the show one boy was still rolling his eyes and glancing sideways at the others. They were laughing. I watched his face shift as he gave up his cynical attitude and decided to enjoy the show.

In one part of the story, I would have to set up a restaurant. The thing about clowning is that you are always onstage, your motives are always transparent to the audience. It was a boring bit, setting up chairs for a restaurant. I thought, “How would a clown do this? The answer was, Badly.” Before the show, I asked the janitor for a stack of ten chairs. When it was time to set the stage, the clown would try to get the chairs apart, and in the process the whole stack would fall over. The frightened clown would not know what to do. She would run to the corner, then tentatively try again but the chairs would fall against each other and make a loud noise. This could go on for a long time until the clown had the sense to ask for help from the strong boys in the back. They had everything set right in no time and went back into the audience to great applause.

In one rural school, I had to play my show in a lobby with a wide hallway. Space was small and crowded with children. I was already dressed as Pierrot the mime clown and had to figure out where I could perform. I put a chair in one place and then moved it to another. The children laughed. The clown looked at them. They laughed. The clown picked up the chair and moved it again. The laughter got larger. The clown and the children played “Where should I put the chair?” for about ten minutes.

Another piece with the younger children of four or five years old in the front of the audience always worked. Pierrot would have difficulty putting on the costume of the Crane. She would helplessly get her arm stuck in the hole for the head, and need a teacher’s help to get it straight. Then Pierrot would put her apron on and try to tie it in the back, which of course was hopeless. A young child would be invited to help her but Pierrot would keep turning around to see what the child was doing. The crowd would yell “Stop!” and Pierrot would stop for a moment until she was curious again. Eventually, a teacher would come to the aid of the young child and the apron would be on and tied.

It was Friday afternoon and I had worked with the children of a rural school for a week preparing scenes from “The Pigs” by Robert Munsch. Pierrot was there to host the show but one class was late and we needed to wait half an hour. Imagine being a mime clown on an empty stage looking at a room of restless children. What would you do? For some reason Pierrot pretended to be pulled across the stage by an imaginary force. The children laughed. Pierrot was pulled back again. The children laughed harder. The room was almost in hysterics by the time the last class arrived. They didn’t know what they had missed.

Popcorn Philosophy

I often think that it is a bit of a stretch from clowning and mime - to humour in the workplace and stress release, to play, to working with the artistic process, to health, but in many ways it’s all connected. When people become stressed and worried, they can forget how to play and their creativity becomes blocked, and so does their productivity. Often even their health is affected. In Japan, the term "karoshi" has been coined to describe death from stress-related diseases, because people are actually working themselves to death. In America, disability because of stress costs employers thousands of dollars.

So being a clown, and doing this kind of work, makes perfect sense. Clowning is about being silly, artfully making mistakes, exaggerating your follies and laughing at yourself. This is just what stressed people need. Laughter is a physical tonic that releases emotions and puts the body and spirit back into balance. Mime creates a dramatic shift in perspective that reminds us the imagination needs an active place in our work if we are going to be able to make creative decisions. Playing with ideas and playing in our environment takes us to every side of a concept and opens new possibilities. The arts offer endless opportunities for play which are sometimes being forgotten - like singing, dancing, storytelling, playing music etc. There is no need to be professional, or to even know what you are doing to have fun playing in the arts. Playing and laughing together builds community and creates stronger relationships. This brings us back to a commonsense notion of health - good humour supports good health. Scientific tests show that laughter supports the immune system and aids in recovery from illness. Everything we need is close at hand, we just need to find ways to access it, and for each person it is a little bit different.

For me clowning and doing all these different kinds of work is connected. The playful approach to life that I have found in clowning is like the root of a tree and humour, health, stress-release, mime, storytelling, puppetry, teaching, facilitating, coordinating, performing, are all branches growing from this one root.

Wolseley Tales: Penny’s Story

Thirty years ago in Wolseley, there were unrepentant hippies, food politics, social justice issues and religious mind sets. People were reading each other’s auras upstairs in Harvest Collective while people were praying on the spot in the basement. They would pray on the spot when someone upset them. There were pregnant women satisfying their urges for peanut butter milkshakes at Mrs. Lipton’s and customers enjoying the new taste of yoghurt and granola. Wolseley was an alternative place. Even before that, Woodsworth, who lived on Maryland, was the Member of Parliament for Winnipeg North Centre during the 1919 Winnipeg strike and the only person in Parliament to vote against participating in the first World war. He said it was the loneliest moment in his life. He could not believe that all those people would send their children to war.

Penny was a Wolseley character. She was a street person. Thin and wiry with short hair, she had a sharp sense of humour and was easily offended. She always wore pants. A lesbian, she would rather be caught dead than wearing a skirt. She seemed to stay young. Growing up in the North End, her mom died when she was eight and she had an abusive father. By her teens she became a street person. She inherited her mom’s china. It was her only memory of her mom, so she gave it to a friend and said, “If I come to you and ask you for the china, don’t give it to me because I’ll sell it for money to buy booze”. She was a tough lady, but she had a dog named Smokey that went everywhere with her. When she moved into Wolseley, she gradually adopted people from the Grain of Wheat church, Harvest Collective and neighbours who became like family to her. She made friends with all sorts of people. She created community by bringing together hippy types, rich people, lesbians, religious people. When she was fifty, she sobered up. She talked of God as “You asshole up there.” She used to say, “Have a nice day unless you have other plans.” When she had been sober for five years she discovered that she had breast cancer. First, she had one breast removed and then the other, so she wore foam falsies. She moved onto Maryland Street where the area was fairly rough. One night she was out at one in the morning and a man tried to assault her. She reached into her shirt and pulled out her falsies and said, “Here take these home and play with them.” He ran away screaming down the street. She told her friend, “I don’t think he’ll assault anyone again.”

She was friends with Mr. Bardell, and he helped her to make her own funeral plans. Through special arrangements with a doctor friend, she was able to stay in a room at the Misericordia hospital as she got weaker and until she died. She didn’t want a priest, she said, “I can talk to the asshole myself!” She didn’t want to be alone by herself so her friends came and spent time with her. One of her neighbours particularly helped her. He said, “I have been a selfish asshole my whole life. I thought, why don’t I try to do something for somebody else, for a change. I want her to die at peace.”

When Penny died, she was cremated. Friends were surprised to find out that at Penny’s request, Mr. Bardell had secretly cremated Smokey when he died a few months before. Penny and Smokey were buried together.

Odds & Ends

Karen Ridd B.A. (Hons.) Child Life Department Winnipeg Children’s Hospital February, 1987

From “There Ought to Be Clowns: Child Life Therapy Through the Medium of the Clown”

Ryan, an eight-year-old boy whose face and right eye had been badly mauled by a dog, was having his dressings changed, a procedure Ryan found painful and frightening. His panic and pain resulted in strenuous non-compliance, which in turn resulted in him being briefly, but forcibly, restrained. The procedure was quickly completed, but Ryan was trapped in a cycle of pain, panic and hysteria, and so impervious to the comforting words of the nurses. Into this deadlock came Robo the Clown. Ryan’s cries abruptly ceased and he moved from wide-eyed amazement to whole-hearted laughing participation in a matter of minutes. The destructive cycle of pain and hysteria had been broken, and when Robo left the room 15 minutes later a cheerful Ryan was playing with his toys.

References

Ridd, Karen. “There Ought to be Clowns: Child Life Therapy Through the Medium of the Clown”. 1987. http://bibliotheque.enc.qc.ca/Record.htm?Record=19133984124919511669

Proctor, Sue. The Archetypal Role of the Clown as a Catalyst for Individual and Societal Transformation. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/977096/