Transformation in Play

Transformation happens in the strangest places.

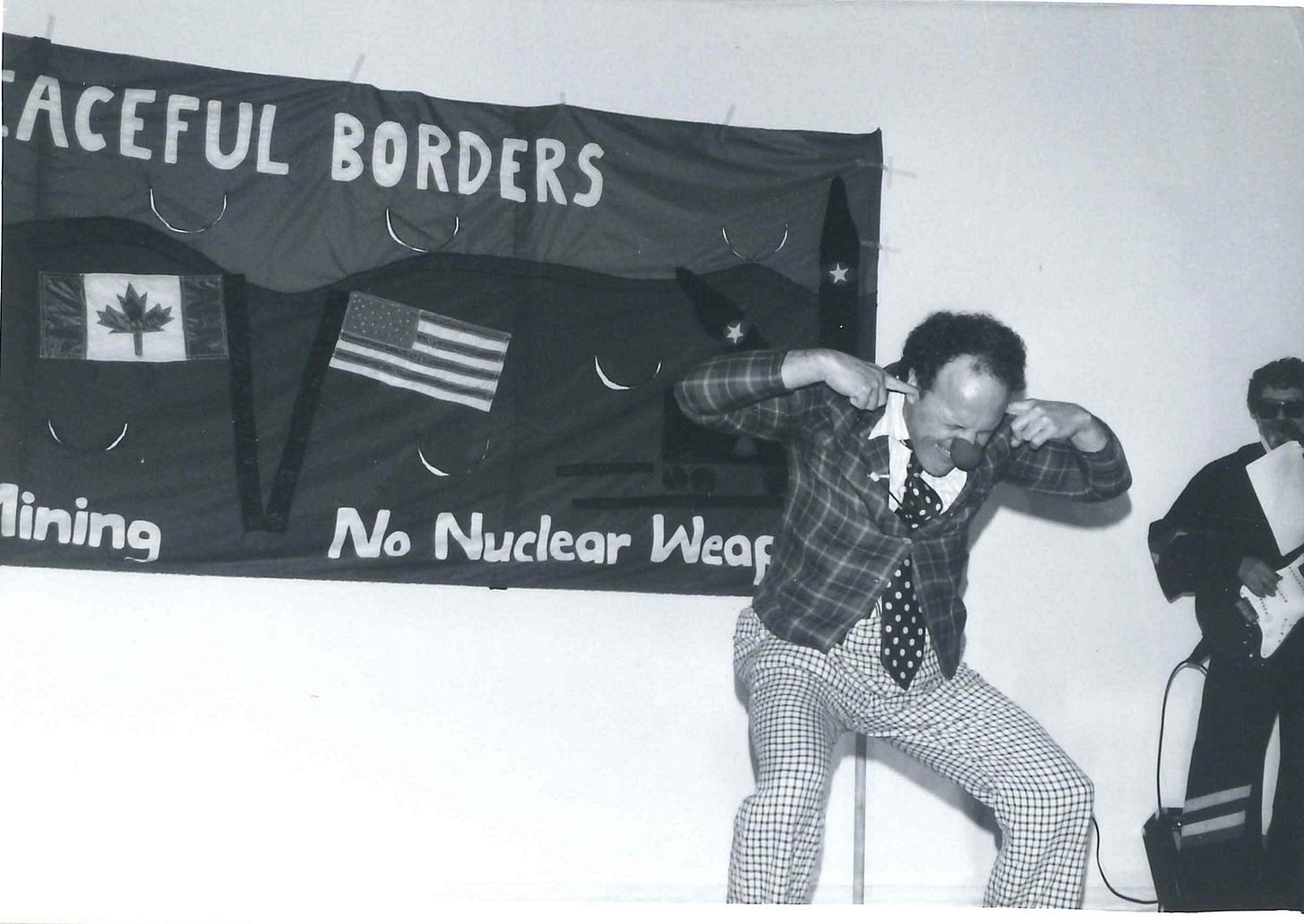

Clowning was leading me into deep waters. The more we clowned, the more the world opened to traditions and concepts that I hadn’t dreamed of. People around the world had clowned for centuries. We were just beginning.

The Hockey Show – On Thin Ice

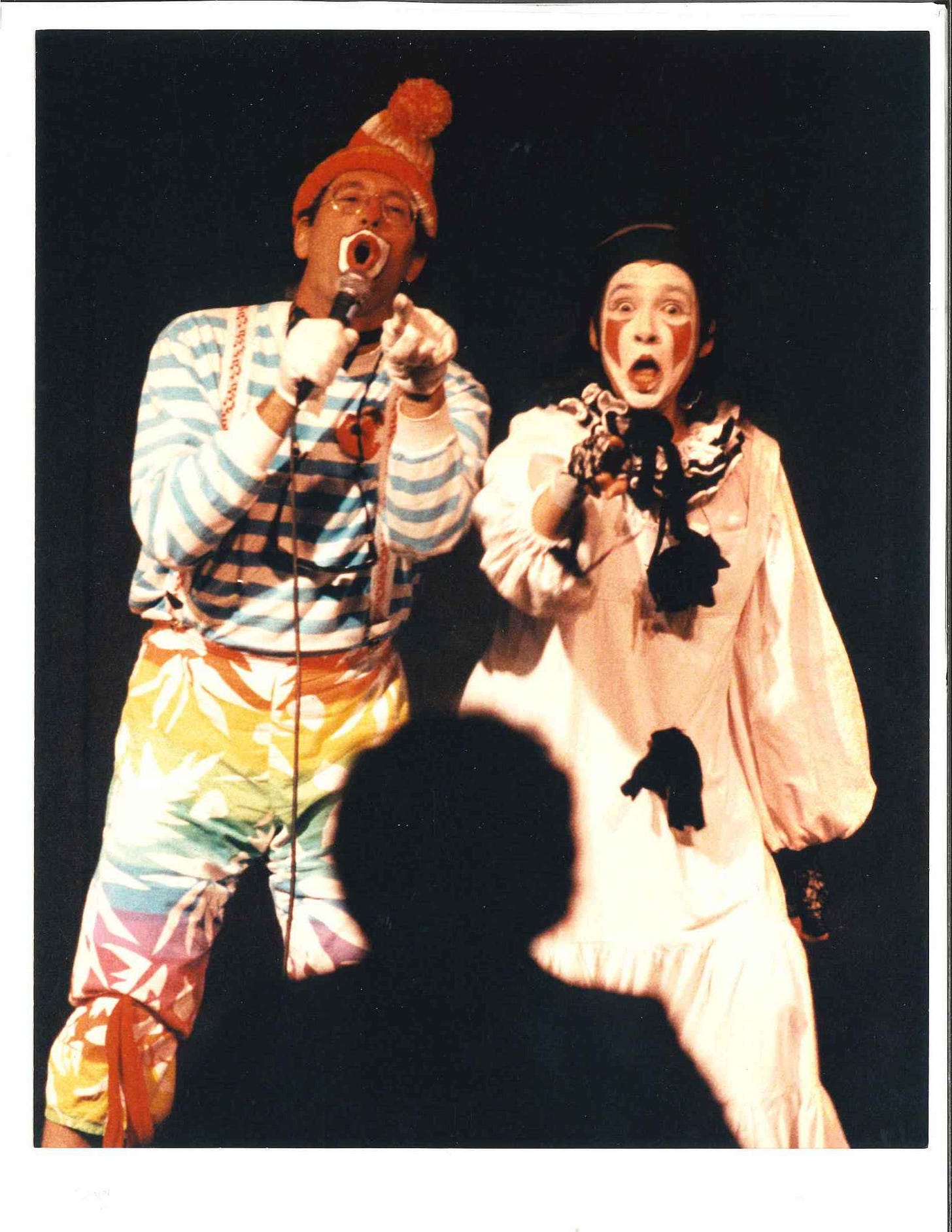

We started the show at the West End Cultural Centre by Mister and Rockbert carrying a couch down the aisle and onto the stage to watch the hockey game. The clowns tend to start where they are, which is onstage and from a genuine feeling. One of Mister’s favorite lines to the audience was – “I’d rather be at home watching the hockey game.” So, he brought the couch to the West End. As the show progresses the clowns are playing hockey and Pierrot is the black and white referee. Rockbert becomes the good guy player and Mister became the Black Center. After a mock battle, they end up doing a Scottish highland dance over the hockey sticks lying in a cross on the stage. Piece reigns.

West End 2

We adapted an old Jewish story where the hero decides to get away from his wife and village and begins a journey. While he is sleeping, someone turns his shoes around. He wakes up and continues his journey but ends up back where he came from. However, he doesn’t realize what has happened and thinks it is another wife and village just like his own.

Mister played the old fool that complained about everyone and everything and went on the journey. Rockbert turned his shoes around while he was sleeping and he returned without knowing where he was. We played it so that he was leaving the clown troupe at the West End Theatre and came back to the West End Theatre #2. He appreciated the other clowns and the audience for the first time.

The good thing about doing a new show a month was that the audience who followed us got to know the characters and could see the humour in relation to the play of the characters.

Popcorn Philosophy

The dual consciousness that I experience as I perform Pierrot makes opposites possible. Jung describes the value of working with paradox: “Therefore, the Chinese have never failed to recognize the paradoxes and the polarity inherent in what is alive. The opposites always balance one another—a sign of high culture” (85). When I clown, I am feeling, experiencing and expressing two things at once—the need for control and success, and the lack of control and absolute failure … which turns into success because the clown’s role is to please us through failure.

When clowns appear in festivals or performances today they often bring a celebratory, carnival spirit. According to Bakhtin: “Laughter proves the existence of clear spiritual vision and bestows it. Awareness of the comic and reason are the two attributes of human nature. Truth reveals itself with a smile when man abides in a nonanxious, joyful, comic mood” (141). When Pierrot, the clown, takes the joke upon herself, the laughter is not derisive and destructive, but accepting and joyous. When this kind of clowning moves into healthcare environments it can become considered therapeutic.

Odds & Ends

Babcock-Abrahams argues that the categories of trickster, clown, jester and fool are expansive categories that cover the gamut from the town jester in medieval Europe to the coyote character present in many Native American cultures.

She asserts that these types of characters, who reverse order, invoke chaos, and epitomize unpredictability, are found throughout the world with little difference between them except the labels scholars place on them.

Drawing on Victor Turner’s notion of liminality and marginality, Babcock-Abrahams suggests that the crucial attribute of clowns and tricksters is their liminal nature. She sees tricksters and clowns as being part of but at the margins of their cultures, expressing the opposite of their cultures’ expected norms; hence their liminal character…. these characters present a necessary dualism and paradoxical nature that allows for “pure possibility.”

Silly Scripts, Stories and Scenarios: Birthday Blues

This was a script that I wrote with Amy. Agnes was a clown and Amy was a puppet body and legs with her own head sitting on the collar and hands coming out of the sleeves. We were new to Covid and to Zoom, so it was a bit of a play on Zoom and all that was happening and being missed in the lockdown. We taped it on Zoom, I guess it’s lying around here som…

References

Babcock-Abrahams, Barbara. "A Tolerated Margin of Mess": The Trickster and His Tales Reconsidered”. Journal of the Folklore Institute 11.3, 1975. 147-186.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and his World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky. USA: The Massechusetts Institute of Technology, 1967.

Jung, Carl. “On the Psychology of the Trickster”. The Trickster: A study in American Indian mythology. Ed. Paul Radin. New York: Bell Publishing, 1956.

Proctor, Sue. The Archetypal Role of the Clown as a Catalyst for Individual and Societal Transformation. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/977096/