Where did all these clowns come from?

Clowning was a wave that was sweeping up the public imagination in a good way.

This clowning movement was getting bigger and bigger. I was falling into a deep well of practice and performance shared by many others. And shared by many other traditions through time. The time was ripe. The public was interested in these fanciful characters and welcomed time to laugh and play.

Nobody’s Fool: But Everybody’s Laughing

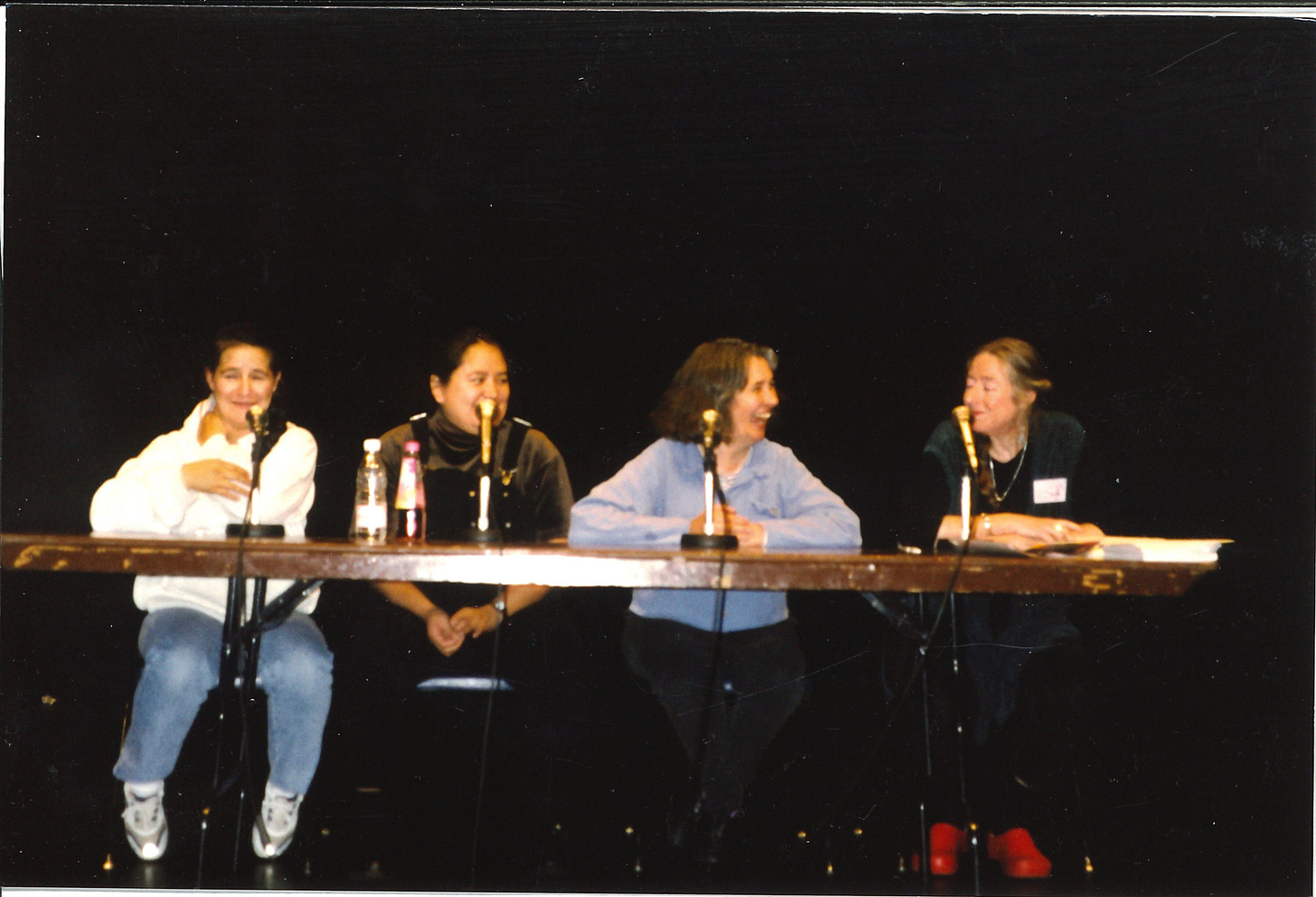

I taught workshops on humour in the workplace, created performances and helped to organize more conferences. It is satisfying to include handouts, memories and articles written about the conferences here. 1997 was the first year at the Gas Station Theatre. 1998 was at the St. Boniface Cultural Centre and 1999 was at the Jewish Asper Centre.

The Gas Station Theatre is a small theatre in downtown Winnipeg. People didn’t quite know what to make of us. It wasn’t Halloween but everyone was dressing up. Shobhana Schwebke (Shobi Dobi), a clown from California who wrote the Hospital Clown Newsletter and who travelled overseas with Patch Adams, came to the first conference and was excellent at Face-painting. Many participants had their faces painted for the first time. At that time, clowning was so much about using costume and make-up for fun and self-expression.

The second conference in 1998 was at the St. Boniface Cultural Centre. This was the first time I realized that clowning is considered differently in each culture. People walking by were interested in the clowns and what we were doing. The francophone public had an affection for the clowns. We brought in Don Rieder and Valerie Dean from ‘Klaunadia’ to teach a workshop on movement and clowning. A portion of the conference was focused on clowning in healthcare because of the pioneering work that Karen Ridd was doing in the Winnipeg Children’s Hospital and we brought together interested clowns from across Canada.

The Best Medicine?

JOHN BAERT, For The Sun

The gathering dubbed a conference on healing and humour, brings together clowns from across North America to brainstorm about the value of a good guffaw and what it means to us all.

“It’s held to explore the art of clowning,” organizer Sue Proctor says. “When we think of clowning, we often are too quick to think of Bozo, and it really is more than that.”

The clown, Proctor says, creates new order through disorder, turns things upside down to renew our vision, reawakens our sense of play and encourages us to heal.

Nobody’s Fool is put on by Clownwise Inc., a Manitoba based non-profit organization which seeks to present performance, networking and educational ideas on the art of clowning and the use of humour to promote community health and well being.

“Clownwise came about through a small group of clowns, social workers and health-care workers who recognized that humour was a very effective window through which to alleviate the stresses and problems in the lives of some of the people we work with and try to help.” Proctor says.

This year’s conference will feature Geri Keams, a Navajo storyteller from Arizona, who will present trickster tales and the Hopi clown (her motto: Don’t Worry. Be Hopi.).

A veteran on the laugh track, Keams credits include work on the film The Outlaw Josey Wales as well as serving as a consultant on the Walt Disney film Pocahontas. Keams was greatly influenced by her grandmother, who taught her the importance of remembering and carrying on ancient tribal stories and chants, some of which she will share at the conference.

Other performers include Doc Willikers, master of medical mirth, doctor of disco and one of a handful of hospital clowns Proctor assembled for the event.

“Clowning in hospitals is a very specific area of clowning,” she says. “Through laughter, clowns are able to help people forget about their troubles for a little while.”

Clowning for Connection

From personal interview with Joan Barrington, March 2011 (cont’d.)

“The fear of the unknown. Often the child does not know who this clown is. Sometimes it takes the child a while to get used to the clown. Sometimes the children come from countries where they don’t know clowns. Then the child life staff might go and read the child a book about clowns and talk to the child about what clowns are. Then the child might see Bunky through the doorway. This might take weeks before the child wants Bunky in their room, or it might take five minutes. You just don’t know, so you have to wait and see. It’s all about them and getting their permission. And then they’re curious and then they’re at the door. I remember one child would sit in a chair, and he would listen for Bunky, but the chair would be turned away from the hallway. He was facing into the room and he would just listen. And then, gradually, I don’t know how many weeks, the chair would start to turn sideways. Isn’t that amazing? And then it would turn a little more. And then it would turn a little bit more, until he could see Bunky. And then his curiosity—he could see through the Lucite of my containers on my trike—he would start pointing to different toys on my trike that he could use. But it’s about taking the time to build the trust.

In the beginning, when I first went to hospital, I had more time to go to rounds. And I felt very privileged to go to rounds. I realized that, at a hospital, like you might have in Montreal or Winnipeg, you’ve got the social workers at the table, the psychologists, you’ve got the child life specialists, the nurses, the doctors, the surgeons—these are the big, important people. And here’s this little red nose sitting there, and I’m going, “Oh my gosh, what do I have to offer?” After a while, I realized I did have something to offer, and I got more comfortable because they would ask me, “Well, how did that go the other day, Bunky? Was the child out of bed? Did they go to physio?” I thought that really legitimized the work, because they would invite me to the table. I felt privileged.

Everyone needs to play. The nurses, you know, ask, “Where are my toys?” They get upset if I don’t leave them a sticker. “Okay, where’s mine?” And they want the wind-up toys going across the nurses’ station. Everybody needs that joy. I can, when I’m going back to the dressing room sometimes, I’ll go in the back hallways where the offices are, and I’ll just stop and wave to someone who’s working at a computer, and they go, “Oh, it’s so great to see you, come on in!” Everybody needs that smile. Yeah.

Or you’re invited to a child’s funeral. It doesn’t get more intimate than that. I thought, “Oh, you want Joan!” No, they want Bunky. The relationship is with Bunky. I walked into the church, the mother immediately came up to Bunky and said, “Come down and see Sally,” and there was Bunky’s picture on the coffin. That was the relationship. That was the relationship. That was her friend. I went, “Okay, that was the right thing to do.” Bunky signed the book, not Joan. I went to the reception in my nose for a bit, and then I left. But that was the relationship. Is that the best? That’ll live with me forever.”

References

Proctor, Sue. The Archetypal Role of the Clown as a Catalyst for Individual and Societal Transformation. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/977096/